Arizona Agriculture Visits with a Veteran Farmer about our Water

Published

6/3/2015

By Julie Murphree, Arizona Farm Bureau: In the complex web of available water for all users, do we make a commitment to preserve agriculture lands? Perhaps, since the irrigated lands of the west can produce almost 4 times as much as dryland watered farmlands in the Midwest. (This article first appeared in the April 2015 issue of Arizona Agriculture, Arizona Farm Bureau's monthly publication.)

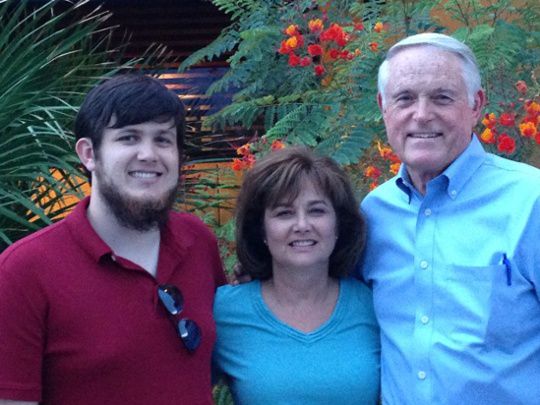

Ron Rayner, here with wife, Heather and son, Ross, is a life-long student of improved practices in agriculture and our vital resources such as water. As one example, Rayner was one of the first in Arizona to develop an effective system of low-till management of cotton, one of the more challenging crops to do low-till or no-till soil management in for areas that depend on irrigation, not dry-land farming.

A third-generation Arizona Farmer, Ron Rayner is a partner in A-Tumbling-T Ranches with his two brothers, Earle and Robert and his nephews John and Perry, growing cotton, alfalfa and grains in the Goodyear, and Gila Bend, Arizona areas. He also farms in California.

With extensive service to agriculture, much of his work has been in the cotton industry. He is a past Chairman of the Board of the National Cotton Council (NCC), after serving as the organization’s president in 1999. The NCC is an organization that encompasses all seven segments of the industry – from production to shipping to manufacturing. Prior to serving as president, he served as chairman of the American Cotton Producers, the grower segment of the Council. He also served as a director and executive committee member of Cotton Council International, the NCC’s export promotions arm and served as a member of Cotton Incorporated’s board.

Since 1999 he has served as a director of Calcot Ltd., a cotton-marketing cooperative for Arizona, California, New Mexico and Texas growers. He served as Calcot’s chairman of the board for four years, retiring from that position this past September. He also is a director and past president of the Arizona Cotton Growers Association.

At home, Ron is an organizing director, stockholder and president of Farmer’s Gin, Inc. in Buckeye, serves as chairman of the Board of Electrical District No. 8; served as member of the Central Arizona Project Board of Directors; and has served as a member of the Arizona Water Resources Advisory Board.

The Arizona Farm Bureau recognized Ron as its Farmer of the Year in 1998. He is a lifelong member of the Maricopa County Farm Bureau and served on the county board. He’s also served as chairman of the Arizona Farm Bureau Water 2000 committee.

Ron and his wife, Heather, and their son, Ross, live in Litchfield Park. He also has two grown daughters and four grandchildren.

Ron has a passion for agriculture and a commitment to seeing this industry continue to thrive despite its varying challenges. He’s developed an expertise in low-till cotton farming and water management. Arizona Agriculture wanted his take on some of the finer points with our water challenges in this desert state. A conversation with Ron Rayner, then, is appropriate.

Arizona Agriculture: On a scale from 1 to 10 (with 10 being perfect), where would you rank Arizona in terms of our water management as a desert state? Please explain.

Rayner: I think I’d rate our management at a pretty high level, like an 8. It doesn’t mean we don’t have problems but our management is quite good.

Part of the reason is that we’ve integrated our resources using both surface water like the Colorado River and Salt River Project with groundwater and water banking for agriculture in-lieu of using our groundwater resources. We have a little resiliency built into the system.

Arizona Agriculture: I’ve heard the quote several times now that “water flows toward money.” Can this hurt our future successes in water management in the state?

Rayner: Well, it’s kind of a tricky question to answer. If somebody wants to outbid you for your supply they can figure out a way to do that. Even in cases where you have a right. They can always bid enough for it that you can become a willing seller.

I just attended the Family Farm Alliance’s annual meeting and that group only deals with preserving irrigated agriculture in the west. Presentations at that meeting underlined that worldwide there are problems keeping irrigation water for agriculture. It becomes the target for expansion of cities. It becomes the target, of course, for drought related issues and supply.

The first thing urban planners think of is, “Let’s see if the agriculture guys will give up some of their production so we can buy from them.”

I don’t know if that’s such a bad thing. If you provide a safety valve so that occasionally, the proper parties can use some agriculture water to get them out of a bad spot maybe that’s okay. It might keep them from trying to take away our water supply through legislation. But, it does create some uncertainty for agriculture and agriculture producers. We have enough uncertainty to deal with in our lives. So, we need to work with these other users of water to occasionally let them buy our water if they need it.

Arizona Agriculture: How do you handle the comment, “Arizona’s agriculture is the biggest consumer of our water!”

Rayner: To grow food requires water. Any growing plant needs water to survive. In Arizona, we do have a year-around growing season and it’s also true we have a very high consumptive use compared to a lot of other areas partly due to our low background humidity level and higher temperatures. The combination of those two creates a higher evapotranspiration rate. Even a swimming pool sitting out in someone’s backyard in Arizona uses six feet of water a year because that’s how much evaporates off of a standing body of water.

The same equivalency is found in a green field transpiring water out through its leaves in our state. So, no question, our crops use water.

But, one of the things we’ve seen in the Phoenix Active Management Area (AMA) is that over time municipal uses of water are the largest users and agriculture is no longer. Several years ago agriculture was the largest user of water in the metro area of Phoenix, but not today.

The West contains approximately 20% of the U.S. farmland but it produces 60% of the total value of the agriculture product we enjoy today. Therein lies the very important message for food security and national security for our country. The cropping systems that depend on rainfall in other parts of the United States may experience more climate variation or weather extremes if predictions are correct. Those areas may be unreliable producers.

In the irrigated west, especially in Arizona, we have very consistent production year after year after year. And, it’s very high production. For example, instead of 45 bushels of wheat like Kansas, we grow 140 bushels of wheat per acre. The area devoted to agriculture in Arizona is very small but it’s incredibly productive. We have a lot of specialty markets like the winter lettuce program in Yuma. It’s a very specialized niche market but it’s very timely when it occurs.

Food security is very dependent on irrigated agriculture. With climate change coming upon us, we’re told, who knows how much more important that aspect may be. We’ve got crops growing every day of the year on our own farm because of the great climate here in Arizona and, due to the fact that we have an irrigated infrastructure. So, while the country might have a drought in Kansas, and we even are in a drought in Arizona, I still have the ability to grow crops because of irrigated agriculture. Every acre on my farm has something green on it today.

Arizona Agriculture: Regarding groundwater use, what are some of our most optimal options to guard against overdraft of groundwater?

Rayner: As upset as many of us in agriculture were with the passage of Arizona’s 1980 Groundwater Management Code, over the years I’ve come to regard it as a very critical part of agriculture’s preservation of water. Because what it did was basically prevented any new uses starting up and pulling water out from under us. It gave us some certainty as to what our rights were -- that we had the right to remove a certain amount of water from the ground each year.

I’m familiar with the Central Valley of California. They just passed a groundwater management act last year but all that act says is, you shall develop basin-by-basin rules to balance recharge with withdrawals and everyone is really petrified because it gives no baseline guarantees. Prior to the law you could drill as many wells as you wanted; you could put new land in production if you wanted.

That has simply not been the case with active management areas in Arizona for a long time now. Our area devoted to agriculture was capped and if it wasn’t in farming in that period just before 1980, it could never be farmed.

A lot of my city friends have no idea this Arizona code is in place. So, if someone sees a piece of desert dirt out there and wants to drill a well on the property and start farming, they can’t. It’s not allowed under Arizona’s Groundwater Code if it’s in an AMA or INA [irrigation non-expansion area].

Arizona Agriculture: You might have heard or noticed Arizona Farm Bureau’s discovery of vast amounts of brackish water underground in our state. What’s your take on this issue? Will technology allow us to economically tap this unused resource?

Rayner: Yes, I read the article. It was very alarming to me. I don’t want anybody using my source of water (he chuckles). That’s what I’ve used to irrigate our crops with all my life. Drainage wells pump water out of the ground 24-hours-a-day, every day in the southwestern quadrant of Maricopa County in Buckeye –– and they send the water to the river bottom.

We then pick up that water down at the Gillespie Dam and we irrigate with it. So, the reality is we’re already using brackish water. We’re just glad now that it’s down to just about 2500-parts-per-million TDS [Total Dissolved Solids]. It’s three times as salty as CAP [Central Arizona Project] water. Growing up there at our Goodyear farm most of that water was 3800-parts-per-million TDS.

We couldn’t grow salt sensitive crops, like vegetables, on our farm. We could only grow salt tolerant crops, like wheat and barley, mainly because you’re growing them in the winter and the cooler temperatures prevented high-salt content water from damaging the plants.

We can grow alfalfa, cotton and winter grains with high-salinity water and do it very well. It does worry me when I see people eyeballing that resource as underutilized.

A recent study looked at trying to set up some kind of a program with the drainage wells in Buckeye to put water through a reverse osmosis system and back up to the CAP canals. If more people tap into this resource the potential for it to be used up faster becomes a factor. The one positive is that the water is located in a shallow water table area so our pumping costs are minimal.

Part of the area where they get some of those really huge “brackish” numbers from is the big saline reservoir under the northeastern Arizona. But, it’s also quite deep from what I understand. If it’s highly saline and in a deep basin, the cost to pump it and then treat it, as of right now is prohibitive.

Beyond brackish or salty water there is the issue of wastewater. More use of wastewater of effluent exists than many water activists think. You don’t see it flowing down the Gila River to the Ocean do you? The Palo Verde Nuclear Power Plant uses about 65,000 acre-feet of water per year from the City of Phoenix’s 91st Avenue treatment plant. Smaller treatment plants produce water that soaks into the ground and becomes part of the recharge of the aquifer.

Arizona Agriculture: Speaking of recharge, how do we use groundwater recharge as an effective tool?

Rayner: Recharge has been a very beneficial part of water conservation. And as mentioned earlier, as users, agriculture and others are actually doing a very good job of recharging this very important resource.

Specifically for agriculture, recharge has been very important in just the last few years because in-lieu of recharge, agriculture users could turn their pumps off and make direct use of a city surface water supply and the city would get the recharge credits for it.

What I’ve believed for years is the best recharge system is the ‘off-button’ on a pump; then find a way to use the surface water directly. For a long time, people thought we had to build these recharge basins when there’s a district just down the road that is running their wells. If you can just figure out a way to let that water district use that water directly and leave the groundwater down under the ground, simply not pumping water from groundwater tables is a pretty good recharge system.

Arizona Agriculture: Do we have a hopeful water future in this state? Please explain.

Rayner: There is nothing more site specific than water issues. It’s hard to make blanket statements because water issues vary from water basin to water basin within the state, wherever you go.

But one of the things that we need to look at, as a policy matter for the state is that water is our limiting resource. We have way more land than we have water. And the idea that you can put houses on even an additional 10% of the land area of this state is foolish.

Water is a finite resource and people are finally beginning to understand that. All the efforts toward conservation, which are certainly okay during a drought when you see it as a temporary matter. You’re not solving a long-term problem, however through conservation.

In fact, farmers and ranchers are being asked to conserve and save water. So, we’re creating the supply for the next wave of houses waiting to be built. One cannot help but react with, “Bring your own water to the table if you want to create a new subdivision.” It’s one of the ways agriculture users can get paid for their property. If they want to go out, they can do a conversion-of-use. But even there you can’t prove a 100-year assured water supply in the Phoenix AMA on groundwater. You still have to buy those recharge credits.

My issue: If you buy those recharge credits to be able to pump groundwater why not buy the surface water and treat it directly and use it from the very first day and just leave the groundwater alone.

Approached this way, it forces us to move up the day when somebody has to go out and look for that next pot of water. Are they going to have to lease it from an Indian tribe or buy it from somewhere else in the state, or retire agriculture land to find it? It makes them face the issue before they get houses planted all over the land. If the cost of a house doubles because of the upfront water cost, the developer will reconsider it. Today making everyone share in that cost is socializing the added cost.

One of the things that most people don’t realize already exists in our laws is an allowance for desalination plants to be built if that’s what it takes to get water to new houses. The Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District (CAGRD) already has the authority to basically pay whatever it costs to buy water to replenish groundwater pumping. The rules allow CAGRD to recover their costs by passing it on to each homeowner’s tax bill in a member subdivision.

It’s happening today. Recharge credits may cost only $140 an acre-foot today, so if a house in Verrado is using an acre-foot per year of water, it shows up on the homeowner’s tax bill as $140 a year for replenishment. If in the future it takes $2,000 an acre-foot of water to get water desalinated for a home, it will show up on the tax bill. The mechanism is already there. Ultimately, it’s putting all of the burden right back on the property owner. I’m surprised more people don’t talk about it. Many of those more recently developed subdivisions will have some very upset homeowners when they find out what they signed up for.

At some point, it wouldn’t hurt for some type of policy issue or a bill introduced into the legislature that says, “We believe the preservation of agriculture lands is important.”

It’s a fine line, but do we want to preserve agriculture lands? Or, do you want to have the right to sell your land and its water rights to the highest bidder?