Crunching Our Agriculture Numbers and Judging the Outcomes

Author

Published

3/19/2024

In the last few weeks, a slate of numbers has come out to mull over. Some of these numbers are sobering, and reflective and might also generate hopeful discussions. First, the numbers.

On February 13th, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) released its 2022 Census of Agriculture report revealing 141,733 fewer farms in 2022 than in 2017. Plus, the number of farm acres fell to 880,100,848, a loss of more than 20 million acres from just five years earlier. No other way to read the numbers exists but that farm numbers and acres in the United States have fallen significantly in five years.

At the state level, Arizona has 2,376 fewer farms (19,086 farms in 2017, and 16,710 farms in 2022 for a percentage decrease of 12%) and 600,732 fewer acres in farming. Possibly until we look at county-specific data, it will be unclear where most of the acre-reduction occurred: cropland, rangeland, tribal land, leased land, or other. Though one line shows the total Arizona “cropland” acres in production at 1,286,648 in 2017 and at 1,221,799 in 2022, a decrease of 64,849 cropland acres, the full picture will require mining the data at a deeper level.

“The latest census numbers put in black and white the warnings our members have been expressing for years,” said American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) President Zippy Duvall. “Increased regulations, rising supply costs, lack of available labor and weather disasters have all squeezed farmers to the point that many of them find it impossible to remain economically sustainable.

“Family farms not only help drive the economy, but they also allow the rest of the nation the freedom to pursue their dreams without worrying about whether there will be enough food in their pantries. We urge Congress to heed the warning signs of these latest numbers. Passing a new farm bill that addresses these challenges is the best way to help create an environment that attracts new farmers and enables families to pass their farms to the next generation.”

A Drop in Farm Income

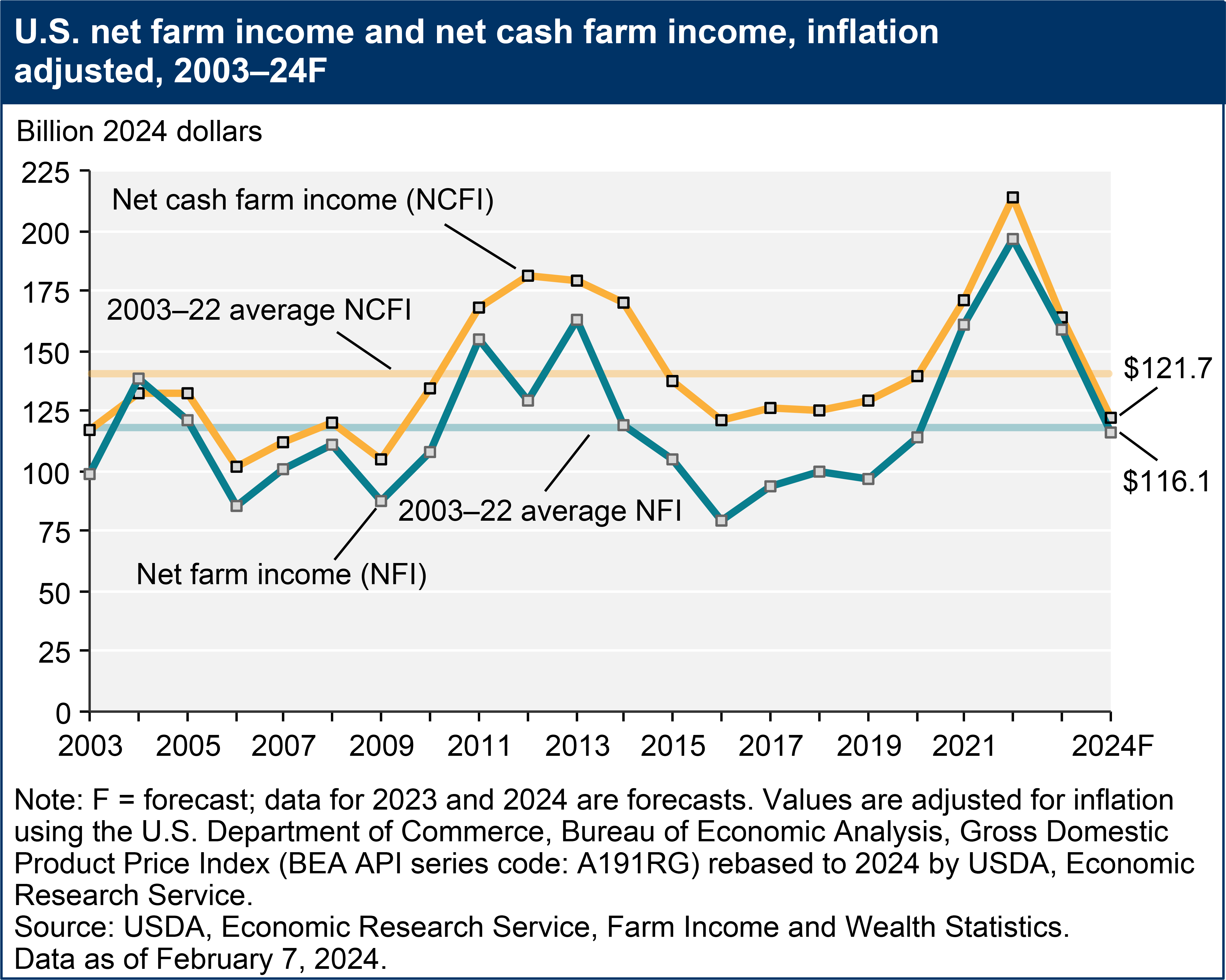

We were already under USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) foreboding news (February 7th) that farm income is forecast to continue to fall in 2024 after reaching record highs in 2022. Net farm income, a broad measure of profits, reached $185.5 billion in the calendar year 2022 in nominal dollars. After decreasing by $29.7 billion (16%) from 2022 to a forecast of $155.9 billion in 2023, net farm income in 2024 is forecast to decrease further from the 2023 level by $39.8 billion (25.5%) to $116.1 billion. Net cash farm income reached $202.3 billion in 2022. After decreasing by $41.8 billion (20.7%) from 2022 to a forecast of $160.4 billion in 2023, net cash farm income is forecast to decrease by $38.7 billion (24.1%) to $121.7 billion in 2024.

In inflation-adjusted 2024 dollars, net farm income is forecast to decrease by $43.1 billion (27.1%) from 2023 to 2024, and net cash farm income is forecast to decrease by $42.2 billion (25.8%) compared with the previous year. If realized, both measures in 2024 would fall below their 2003-22 averages (in inflation-adjusted dollars).

Tight Cattle Inventories for the Foreseeable Future

Says AFBF Economist Bernt Nelson, “USDA’s January and July Cattle Inventory reports, released toward the end of each respective month, provide the total inventory of beef cows, milk cows, bulls, replacement heifers, other steers and heifers, and the calf crop for the current year. With drought and high input costs compelling farmers to market a higher-than-normal percentage of female cattle, the most recent cattle inventory dropped to lows not seen in decades. This Market Intel will provide an analysis of the Jan. 1 inventory, which will set the tone for cattle markets in 2024.

“This is a bullish report. All cattle and calves in the United States on Jan. 1, 2024, were 87.2 million head, 2% lower than this time in 2023. This is the lowest Jan. 1 inventory since USDA’s 82.08 million estimate in 1951 (Figure 1). The calf crop is estimated at 33.6 million head, down 2% from last year and the smallest calf crop since 33.1 million in 1948.”

Nelson’s report goes on to lay out clearly what’s going on in the cattle market. He summarizes with, “USDA’s semiannual cattle inventory report provided some key insights for cattle markets in 2024. The overall cattle inventory, along with the beef cattle inventory, is historically low, yet the supply of cattle on feed is quite large. The calf crop and beef heifers held for replacement are also historically low, which will hinder cattle inventory growth in 2024 and possibly 2025. This should provide opportunities for profitability in the cattle business in 2024, but with a smaller calf crop and fewer replacement heifers, declining production may also lead to record beef prices for consumers. Domestic consumer demand for beef has remained strong but with record prices on the horizon, consumers’ ability, and willingness to withstand higher price levels in 2024 will be the determining factor.”

Hopeful Reflections

In Arizona and across America, in agriculture, we’ve learned to do more with less for generations. These numbers show we must still do just that out in farm and ranch country. We certainly have confirmation of how efficient and productive we are with less water if you read this issue’s “Conversation” article on page one of the publication.

To emphasize the main point of UArizona’s George Frisvold’s study, “In the Lower Basin that includes Arizona, farmers used 1.2 acre-feet on average to produce $1,000 of crops. In the Upper Basin, farmers used more than 7.6 acre-feet. Within the Lower Basin, the water footprint is even lower in the Southwestern half of Arizona. We also looked at gross farm income net of crop-specific costs. Four counties, Imperial and Riverside in California and Yuma and Maricopa in Arizona, accounted for 75% of regional net crop revenues while consuming less than half of the Basin’s irrigation water. If you also include Pinal, La Paz, Graham, and Cochise counties in Arizona, these eight counties accounted for 90% of crop net returns and two-thirds of irrigation water consumed.”

In all of this, we haven’t even addressed the inflation numbers in this article. Inflation on the farm is worth noting since every input cost has risen on average in the double digits. On the consumer side, overall prices have surged by on average 18% since January 2021. At every turn, Americans are paying with dollars that have less value than they did in 2020.

What is our “hopeful discussion?” Our discussions on the ditch bank, in county Farm Bureau meetings, at water meetings, and in testimony before legislative committees reflect and represent an industry known for how productive Arizona is as an agricultural state. Those discussions happen naturally even from non-agriculture voices when they show the charts, the history and the evidence of what Arizona agriculture has done for Arizona.

Today’s numbers are tough. So, you’ll find farmers and ranchers reassessing their budgets, possibly diversifying their crop and livestock portfolios even more, and recalibrating. For all of us, we must celebrate our farms, ranches, and dairies. And don’t forget, we need to push for and then cheer on the passing of a farm bill this year.

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of Arizona Agriculture.