Meet Arizona Agriculture's Harold Payne and Fort McDowell Farms

Published

8/4/2015

By Julie Murphree, Arizona Farm Bureau: As their website says, “The Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation is a 950-member Native American tribe that calls Central Arizona’s upper Sonoran Desert home. Located to the northeast of Phoenix within Maricopa County, Arizona, the 40-square mile reservation is a small part of the ancestral territory of the once nomadic Yavapai people, who hunted and gathered food in a vast area of Arizona’s desert lowlands and mountainous Mogollon Rim country. It’s in this setting that Harold Payne has managed the 2,000-acre farm for more than 20 years.

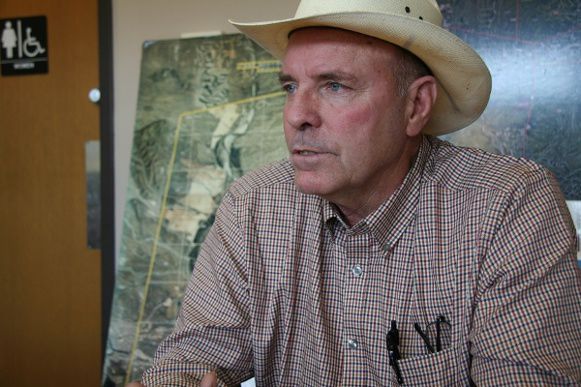

An interview with Harold Payne of Fort McDowell Farms.

Part of an ongoing series about Arizona Farming and Ranching Families.

Talk about Fort McDowell Farms: We have 2,000 acres in production. Half of that is pecans, as well as 300 acres of citrus, and the remainder farmed is alfalfa and barley. We are on about 25,000 acres (4 miles long and spans 12 miles wide) of the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation. The land is near Fountain Hills and the Ft. McDowell casino. Our citrus ranges between five different types: primarily lemons, tangelos, tangerines, navel oranges, and grapefruit.

Harold Payne

The Yavapai tribe has been farming this area since the 1980s. The reservation was given to them in 1939. In the early

If you go way back, this land was farmed in the 1800s by Hispanic families, growing alfalfa for the U.S. Army horses.

So what is your background? I come from farming. I was born in New

How do you see the future farming in Arizona through your vast experience in the agricultural industry? A lot of the future of agriculture in our area is in the hands of the Indian reservations, as they have been assigned most of the available agricultural water. The Gila Indian Reservation owns about

Would you ever consider growing an emerging crop or changing your farm model?

Because of the limited water availability, you can’t really expand the agriculture revenue stream on behalf of the tribe, correct? Only if we switched to a higher-value crop. We could develop more

What’s your market for that barley? We generally have contracts with Arizona Grain; it goes into the feedlots and the dairies. That’s the amazing thing about barely. Barley is very productive as far as the cash flow and revenue because planting one semi-load of seed in November results in 70 semi-loads back. All of that happens in five months, so that’s a good return on your money. It’s just one of the many reasons I love agriculture. I look at agriculture as a miracle, the combining of water,

If you look at our farm right now, we have nothing to sell [Interview conducted during dormancy of the citrus orchards]. The hay is in the field awaiting warm weather, the barley is growing steadily, and the trees are dormant. Come back a year from now, and we will have sold 13 million pounds of products from this little property. Two million of that are pecans, four million in citrus, and the rest is barley and alfalfa.

What do you see in the future knowing that water is probably your only constraint? Well, we are pretty stable because this river has never been dry in the history of mankind. The Verde has always had water in it. We have a really good water shed located upstream from the farm -- there are two dams on the Verde River, and SRP is very diligent in how they operate them.

People don’t realize how neat agriculture is in this area, especially when most are floating down the Salt River just a few miles from here… We are kind of an untold story of a Native American Tribe developing their resources to become self-sufficient. The nice thing about the farm is that it is sustainable, and it is permanent. Although, the tribe has thought about diversifying into more enterprises.

Although in agriculture there can be tough years, you can say that you have had profitable years for them? We have actually never lost money on our operation, but there is no guarantee that losses could not happen here. We are self-financed so we do not have to borrow money from anyone, and we keep what the farm needs to operate, and then the rest goes back to the tribe.

With Agriculture in Arizona shifting, do you see agriculture growing, shrinking, or staying the same size wise in the future? I see it shrinking, for several reasons. One