A Destiny Fit for a King

Author

Published

10/29/2019

Way back in 1885, a young Manuel King was hired by a large cattle outfit from California to drive a herd of cattle out to the Altar Valley in southern Arizona (35 miles southwest of Tucson). Convincing his bosses he was a strapping 18-year-old (in reality only 17), he “cowboyed” for the California company for several years until they went bankrupt.

For Manuel’s final payment, he gained a cattle herd. Thus, began the legacy of the King ranching family in southern Arizona.

But back in the late 1800s, the burgeoning family was simply trying to make a living in ranching. While Manuel’s family was not initially known as cattle people, with his new herd he headed to Brown Canyon in the Altar Valley to homestead. Over the years he bought out the other homesteaders around him; at the time he also began courting a young woman, Margaretta, who was teaching children at a neighboring ranch.

The young couple married, and Margaretta and Manuel King raised five children, two girls, and three boys.

The Kings characterized the Arizona ranch family at the time. According to historians, while stock raising in Arizona began as early as the 1690s with Spanish settlers and missionaries, large-scale ranching did not really take place until after the American Civil War in 1865, when conditions were more favorable partially because the U.S. Army and seasoned war veterans were now available to protect a growing nation flung out across the northern continent.

As a result, cattle numbers in Arizona quickly grew. In addition, the windmill, which was used to pump groundwater into storage ponds, and two transcontinental railroads across Arizona enabled large capital investments by businessmen seeing profit in the growing beef markets.

Manuel, in fact, came over by train with the initial cattle herd and then from the train station had to drive them to their destination in southern Arizona. The livestock he managed were part of the 1.5 million head of cattle in the early 1890s, along with more than a million sheep, that roamed the Arizona landscape. Just two decades earlier cattle numbers were no more than 40,000.

Old pictures of the ranch and the Altar Valley area reveal a somewhat different landscape than what the most recent generation of Kings are used to. The Kings’ Anvil Ranch benefitted from plentiful mountain rain runoff during this time. You could walk a horse in front of the floodwaters they were so mild and slow as the water moved down a mile-wide floodplain. Indeed, historians report favorable climate conditions that enabled healthy and bountiful forage to grow. Manuel King described it as “a sea of grass because of the floodwaters that came down from the mountains.”

Of course, severe droughts and other climate conditions changed the landscape. Plus, large landscape fires that kept shrub and mesquite encroachment in check were stopped. And most concerning, with the growth of larger herds, the reduced precipitation meant cattle were overgrazing the open ranges, helping destroy shared pasturelands.

Arizona history marks 1891 as Arizona’s biggest calf crop during that time; in the interim less than one-half of the average rainfall soaked the ground. Dry years continued after that with 1893 marking the first recorded drought to have major impacts on the cattle industry in Arizona. The southern Arizona cattle population was decimated with up to 75% of all livestock dying. What was left was raced to market where prices plummeted. Only the hardiest of ranchers stayed. The King family was one family that prevailed and began taking steps to manage their herds under these new conditions.

Range Management and Generational Commitment to the Land

“The family has always cared about the animals, the water and the land,” says Micaela McGibbon, the oldest sibling of three King children to parents John and Pat King.

But back in the late 1880s, the burgeoning family was simply trying to make a living in ranching. While Manuel’s three sons ranched together for some time the brothers eventually split off into two ranches with Micaela’s Grandpa John and Great Uncle Joe forming King Brothers and running Anvil Ranch. Great Uncle Joe eventually moved to Red Rock to ranch.

Grandpa John F. King had one son, named John W. (Micaela’s dad), who now runs Anvil Ranch. John’s children are Micaela, John, and Joe.

Micaela remembers her dad telling stories about Grandpa King describing “neighbor round-ups.” She describes stories about how everyone used to gather when the range was unfenced between ranches. “They’d begin with round-ups that would start in Sasabe and head north all the way to Red Rock. Neighbors along the way would join the round-up, ride their part of the valley and gather and brand all the cattle. Since I’ve been little we never have gathered with our neighbors so these stories are unique to me.”

Back then, cattle were typically sold at three and four-years-old. Arizona was lacking the modern-day feedlots to finish a cattle’s weight for market. Cattle were often much wilder; untamed by man’s influence and handling.

The King family began to recognize the need for better range management while holding on to their heritage as a ranching family.

Quoting from an article recently done by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), “The long-term history of the ranch is interesting and carries great value,” said Joe King, youngest of John and Pat King’s children. “We know what the ranch was like before us and what it is capable of being. Ranching is what we do.”

Adds Micaela, “I feel that my family has actual roots and are well-grounded. We know where we came from. I was raised in the same place my dad was raised and grandfather and great grandfather. We feel it’s our calling. We enjoy the land, the animals, and the work.”

To begin addressing times of severe drought, supplementing water sources and managing grazing lands, John’s father, John F., began working with the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) in the 1950s during the Mid-Century Drought that lasted from 1942-1978.

In the 1960s and 1970s John F. expanded its NRCS conservation plan to include brush clearing. The King family worked hard to remove mesquite trees that provided too much shade for native grasses to germinate and grow, reducing the amount of vegetation available.

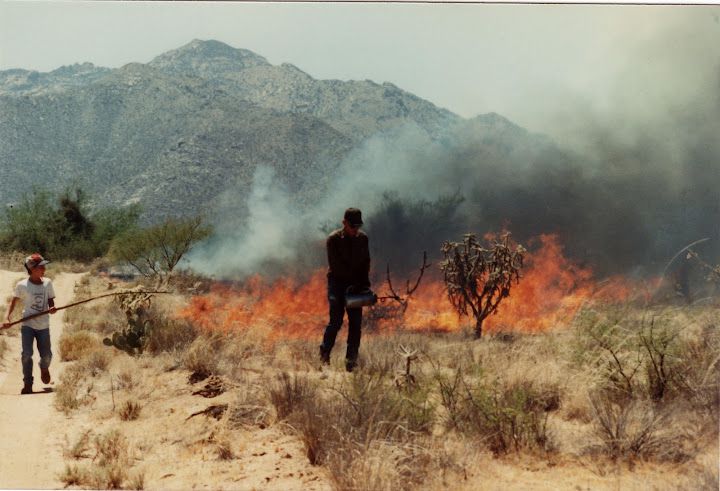

John P. (son) and John W. (father) are seen here in the 1980s conducting a prescribed burn just before the summer rains to let the pasture rest for two growing seasons. The Kings were able to burn about one-fifth of the ranch, or 12,000 acres, between the years of 1985 and 1997 and had a great program established until they were stopped by the Endangered Species Act. The result of the burning had a dramatically positive impact and has been well documented by monitoring transects and pictures. Not only did the ranch recognize the benefit of the fires, but hunters would also stop by and ask where we had burned. They found greater numbers of all game on the newly burned areas. We also observed that many ‘endangered’ plants and animals seemed to thrive in these rejuvenated grasslands.

“One of our more challenging goals has been the reduction of mesquite, noxious plants and other encroaching shrubs,” says Micaela’s younger brother, John. “Working with NRCS, we utilized chemical, mechanical and fire. We found fire was the most cost-effective. By setting aside a pasture for one entire year, we burned just before the summer rain and let the pasture rest for two growing seasons. We were able to burn about one fifth, or 12,000 acres, between the years of 1985 and 1997 and had a great program established until we were stopped by the Endangered Species Act. The result of the burning was dramatically positive and has been well documented by monitoring transects and pictures. Not only did the ranch recognize the benefit of the fires, but hunters would also stop by and ask where we had burned. They found greater numbers of all game on the newly burned areas. We also observed that many ‘endangered’ plants and animals seemed to thrive in these rejuvenated grasslands.”

“There wasn’t any cross fencing at that time either, so we worked with NRCS to put up fence,” said Pat King. “We continued to do so through the 80s and began our pasture rotations. Before we had cross fencing, it took time and a lot of manpower to round-up the animals, count them and feed them.”

The installed fencing improved the management of grazing lands by leaps and bounds. But the family also had to address the water issue allowing cattle better pastures.

Water needed to be delivered to where livestock grazes, or where it’s desirable to have the livestock located, rather than requiring livestock to travel long distances to drink. While the ranch had a few stock ponds that would fill when it rained, the process was not efficient. The King family used funding from the NRCS Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) for installation. Over the past 18 years the Kings have added more fencing and more pipelines all for the purpose of improving their grazing management plan.

Through all this, the King family has also added solar technologies to pump water at their ranch. One of their largest solar systems pumps seven to eight gallons of water per minute. This is more than twice as much compared to old generators previously used.

“The solar pumps are great. There is less maintenance required and they save us a lot of money,” said Joe King. “They paid for themselves in the first two months.”

“The ranch has private, state and federal lands. But to us, the land is ours. It doesn’t matter what land it is, its condition is what defines the kind of ranchers we are. Maintaining a good functioning habitat is important to us,” added Pat.

A Childhood Remembered

“Since the age of 14, I remember that we didn’t have a lot of help on the ranch, so my brothers and I joined in with our parents and we did it all,” remembers Micaela. “For one, we were pretty secluded. We woke up early morning and worked on the ranch the entire time.”

She goes on to share her parents’ commitment to improve the efficiencies of the ranch which included the cross fencing. One memory she recalls was putting up three miles of fence in just three days.

“Of course, some of the best times we’ve had were working as a family,” she said. “I didn’t need to go on vacation because I got to see my family all the time. I felt like I knew my father better than any other kid because I was with him on the ranch all the time. My parents made ranching a family affair. It wasn’t just dad’s business, it was our business. What’s been interesting is all three of us have continued on as ranchers.”

So, while John, their father, might come off as a quiet, unassuming rancher, to his kids he was a very engaged father. “I’m the oldest and the only girl so mom would always threaten me with housework, so I’d always run outside and help dad.”

Why such a work ethic? If you’re in agriculture, you don’t even have to ask. For so many farm and ranch families the work is simply part of the ethos of the family.

Take this generation’s effort at improving the land and cattle including dealing with a lack of available labor. Some of the new structures to their farming and ranching, like cross fencing and strategically piping water to specific pastures, not only improved land and cattle management but meant fewer would have to help on the ranch.

In the old days, a large ranch could have as many as 12 cowboys gathering stray cattle over a big expanse of land. But by the time Micaela’s dad took over the Anvil Ranch, he only had 2 cowboys. In the King’s particular setting, they could also compensate for lack of employees by building infrastructure and working as a family.

“As any ranch family looking to improve will tell you, we’re always looking for efficiencies in how we raise our cattle,” says Micaela. “Cross fencing is basically cutting up land areas into manageable working pastures. On the breeding side of it, we selected cattle for genetics and temperament. Because of cross fencing, you must constantly work the cattle to make them gentle.”

She describes her summers growing up. “Every morning I’d go out, saddle up, and go out and ride through the heifers on the ranch. It’s redundant, it’s repetitive, but it has to be done. You get to know the animals and they get to know you. The only downfall is that pushing your cattle is like pushing a wet noodle. But, on the other hand you don’t have to run and chase them everywhere. That’s just how we chose to work our cattle since there were only four of us.”

John W. King and Joe King head out for fall round-up, a part of ranching life as generationally consistent as the seasons.

Ranching for the Kings is a business. As a family, they work to make a profit. “However, we treat our animals as if they are our family,” says Micaela. “We are providing for others. We feel God put us in this line of business for that reason. Any rancher will tell you, it takes a strong personality to handle hard-headed cattle.”

The Kings Today

Today, Micaela, John, and Joe are fully engaged in the Kings’ ranching tradition. Joe and his wife, Sarah, are managing the Anvil Ranch while raising a girl and boy; John and wife, MaRae, have five children and are ranching in New Mexico; and Micaela and husband, Andrew McGibbon, are managing their family ranch east of Green Valley with their three girls and one boy.

When Joe King married Sarah Henckler in 2011 the three generations gathered, representing the ongoing tradition of ranching in the King family. All three King children, Micaela (second from left, back row), John (third from right, back row) and Joe (center), are currently ranching full-time. (Photo courtesy of Roni Ziemba.)

The King family are core members of the Altar Valley Conservation Alliance, where Pat serves as president. Sarah is the Community Outreach and Education Coordinator for the Alliance. Nearly all of them serve in leadership positions in Arizona Farm Bureau and Arizona Cattle Growers.

The Kings have opened their home to many to experience the lifestyle of ranching on the Arizona and Mexico border. One ongoing commitment by the King family is to educate politicians and the public on the issues they face.

Maybe the King family history didn’t start by simple chance. Maybe Manuel’s destiny was written down all along. And just maybe the next 100 years of Arizona’s history and the King family’s history in this state will continue to forge a future celebrated by all the generations to come.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in 2012 as part of a historical series on Arizona’s 100 years of statehood and its agriculture history. We publish it here with minor updates.