Beef Arizona Agriculture Style

Published

11/12/2013

By Julie Murphree, Arizona Farm Bureau: Historically, Arizona agriculture’s beef story is compelling enough. Many of our fifth and sixth generation ranch families in this state got their start in the industry back in territorial times by supplying quality beef to the U.S. Army.

According to historians, while stock raising in Arizona began as early as the 1690s with Spanish settlers and missionaries, large-scale ranching did not really take place until after the American Civil War in 1865, when conditions were more favorable partially because the U.S. Army and seasoned war veterans were now available to protect a growing nation flung out across the northern continent.

As a result, cattle numbers in Arizona quickly grew. In addition, the windmill, which was used to pump groundwater into storage ponds, and two transcontinental railroads across Arizona, enabled large capital investments by businessmen seeking profit in the growing beef markets.

Livestock managed in the early 1890s ran as large as 1.5 million head of cattle, along with more than a million sheep, roaming the Arizona landscape. Just two decades earlier cattle numbers were no more than 40,000.

Severe droughts and other climate conditions changed a previously lush with grasses landscape. Plus, large landscape fires that kept shrub and mesquite encroachment in check were stopped.

Arizona history marks 1891 as Arizona’s biggest calf crop during that time; in the interim less than one-half of the average rainfall soaked the ground. Dry years continued after that with 1893 marking the first recorded drought to have major impacts on the cattle industry in Arizona. The southern Arizona cattle population was decimated with up to 75% of all livestock dying. What was left was raced to

Arizona’s unique desert climate in the southern part of the state might be part and parcel why Arizona agriculture’s beef industry can lay claim to some unique features in our ranching business in the state.

Beef Arizona Agriculture Style

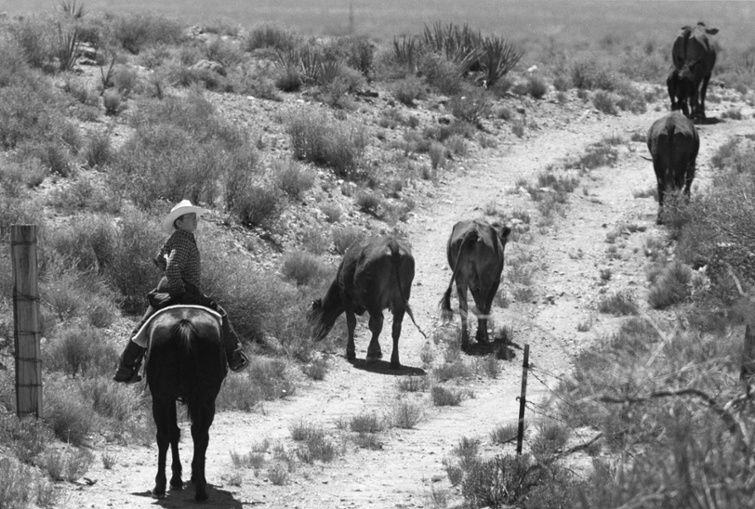

The fifth-generation King family of Anvil Ranch in Pima County typifies Arizona’s long-standing ranch families.

Quoting from Arizona Farm Bureau’s Arizona Agriculture 2012 publication, “The family has always cared about the animals, the

Micaela remembers her dad telling stories about Grandpa King describing, “neighbor round-ups.” She tells stories about how everyone used to gather when the range was unfenced between ranches. “They’d begin with round ups that would start in Sasabe and head north all the way to Red Rock. Neighbors along the way would join the

The King family recognized the ongoing need for range management back then while holding on to their heritage as a ranching family.

Quoting from an article done by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), “The long-term history of the ranch is interesting and carries great value,” said Joe King, youngest of John and Pat King’s children and currently president of Pima County Farm Bureau. “We know what the ranch was like before us and what it is capable of being. Ranching is what we do.”

Adds Micaela, “I feel that my family has actual roots and are well grounded. We know where we came from. I was raised in the same place my dad was raised and grandfather and

“One of our more challenging goals has been the reduction of mesquite, noxious plants and other encroaching shrubs,” said Micaela’s younger brother, John. “Working with NRCS, we utilized chemical, mechanical and fire. We found fire was the most

“There wasn’t any cross fencing at that time either, so we worked with NRCS to put up

All the King family’s efforts meant better land conservation and a better legacy for their family including producing quality beef for the markets.

The Value Cattle Bring to the Land

The King family’s tradition of caring for the land and their cattle is what you typically find with Arizona’s ranch families.

Another ranching family with five and six generations of Arizona ranching families on both sides, the

Tomerlin, whose heritage breed of cattle, Criollo (

And on the value of cattle, the

Patrick Bray, executive director

Speaking of Arizona’s cattle market, Bray highlights that the cow herd and calf crops are at all-time lows. “Although we have seen this at other points in history, the market in which we compete today is highly sophisticated compared to the old horse and rope. Today, ranchers can watch and purchase from live cattle sales

Bray and others go on to explain that while any gathering of ranchers may focus on market prices, the techniques of monitoring changes in the landscape and stewardship also dominate the conversations. One important program is the University of Arizona Extension’s program called “Reading the Range” for a few years collecting data to monitor trends and to assist producers in making critical decisions regarding grazing rotations.

Ultimately, a combination of tradition and technology advances are helping Arizona agriculture’s ranch families make a difference in their futures and ensure quality Arizona beef.